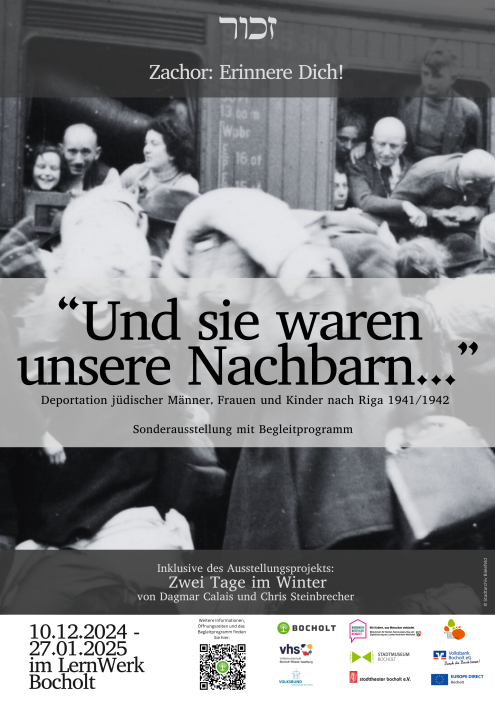

And they were our neighbours

About the exhibition

From 10 December to 27 January, the city of Bocholt is presenting the exhibition "And they were our neighbours... - Deportation of Jewish men, women and children to Riga 1941/1942" at the LernWerk.

The exhibition focuses on the deportation and fate of Jewish citizens from Bocholt who were deported to the Riga ghetto in 1941. One focus is on the events in the Riga ghetto, where thousands of Latvian Jews became victims of mass murder.

This is where the exhibition "Zwei Tage im Winter - Zachor: erinnere dich!" by the Bremen artist couple Dagmar Calais and Chris Steinbrecher comes in, which is also part of the exhibition programme. It shows the effects of the National Socialist extermination policy on the Jewish population in Latvia and the Jewish citizens of Bocholt.

Opening in the new artist appendix of the LernWerk

This exhibition is the first in the LernWerk's new Artists' Appendix and is funded by the "Heimat-Fonds" of the Ministry of Regional Identity, Communities and Local Government, Building and Digitalisation of the State of North Rhine-Westphalia and Volksbank Bocholt eG.

The city of Bocholt is realising the exhibition in cooperation with the Bocholter Kunst- und Kulturgemeinschaft e.V., the Stadttheater Bocholt e.V., the Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge and Europe Direct Bocholt.

Admission to the exhibition and participation in guided tours are free of charge.

Accompanying programme to the exhibition

| date | Time of day | Programme item |

|---|---|---|

| 12 January 2025 | from 11 am | Lecture by Europe Direct Bocholt on Jewish culture in Europe in the LernWerk appendix (admission free) |

| 17 January 2025 | from 7 pm |

Concert "A Liedele in Yiddish" by Stadttheater Bocholt e.V. in the large event hall of the LernWerk (tickets for 25 euros at www.stadttheater-bocholt.de) |

| 27 January 2025 | from 7 pm |

Musical reading from the book "I survived Rumbula" by Bocholt City Library in the LernWerk appendix (free admission) |

Jewish life in Bocholt

© Stadtarchiv Bocholt

View of the Löwenstein family's shop in Osterstraße.The earliest mention of Jewish life in Bocholt dates back to 1562, when a Jewish medical student was granted the right of residence for the town of Bocholt.

In 1852, the Bocholt synagogue district was founded, which included the Jews from Anholt, Dingden, Liedern, Rhede and Werth in addition to the main community of Bocholt. One year later, 21 Jewish families were registered in Bocholt.

In 1932, there were 12 manufacturers, 35 merchants and 17 craftsmen, including 7 butchers, of the Jewish faith in Bocholt. The economic importance of the Jewish factory owners for the economic power of the city of Bocholt is demonstrated by a formulation from the city administration in a letter dated 17 January 1931 to the district president of Münster regarding the continuation of the Israeli school. The letter points out that the city's tax revenues are very high, particularly due to the flourishing businesses owned by Jews. The school must therefore continue to exist.

Josef Niebur,

Book of Remembrance. Jews in Bocholt.

1937 - 1945, Bocholt 2013, p. 61.

In 1932, around 220 people belonged to the Jewish community in Bocholt. This made it the second largest community in Münsterland after Münster and represented just under 1 per cent of Bocholt's population. Despite their relatively small number in relation to the overall population, Jews also played a decisive role in shaping social life in Bocholt.

They were politically active, established associations, set up as doctors or tradesmen, founded companies and built their own synagogue, Israelite school and cemetery in the town. Naturally, Jewish members of the Bocholt community also fought for the German Empire during the First World War.

The situation after the First World War

© Hermann Oechtering

A memorial stone was erected for the fallen in 1964 at the Israelite cemetery on Vardingholterstraße.The Jewish community of Bocholt mourned a total of eleven losses among its members at the end of the First World War.

Gottfried Albersheim, Erich Braunschweig, Fritz Gompertz, Paul Hochheimer, Paul Löwenstein, Julius Metzger, Dr Erich Rosenberg, Otto Rosenberg, Gustav and Siegfried Sander from Werth and Walter Wolff.

With the promulgation of the Weimar Constitution in 1919, Article 136 gave Jews full equality with the rest of the population. All state offices and civil rights were henceforth to be available to them without restriction.

In the first free, secret and equal local elections on 3 March 1919, Emil Cohen was elected to the city council in Bocholt. Jeanette Wolff, Emil Cohen and Richard Friede stood in the 1924 municipal elections. They belonged to Bocholt's Israelite community.

In retrospect, the years from 1924 until the great global economic crisis of 1929 are regarded as the "golden years" of the Weimar Republic. In this environment, Judaism was also able to flourish politically, culturally and religiously. Various associations such as the 'Association for Jewish History and Literature', the travelling association 'Kameraden' and the 'Reichsbund jüdischer Frontsoldaten' were founded in the aftermath of the World War. The local group in Bocholt, led by Bertold Löwenstein, began its work before 1922.

%20war%20von%20M%C3%A4rz%201919%20bis%20zum%203.%20januar%201932%20mitglied%20der%20spd-fraktion%20in%20der%20bocholter%20stadtverordnetenversammlung..jpg?height=444&width=296)

©

© Maik Haines

Anti-Semitism in the Republic

As much as Jews wanted full legal and social recognition and equal rights after the end of the First World War, anti-Semitic tendencies never completely disappeared. There were repeated attacks on Jews in the Republic.

The anti-Semitic activities were channelled by "patriotic" politicians who had no interest in the democratic reforms of the newly founded republic. Rather, they had lost some of their privileges and were now committed to fighting against the republic and democracy. They had many means at their disposal, including the use and dissemination of anti-Semitic prejudices. In 1919, for example, the Deutschvölkischer Schutz- und Trutzbund was founded as the largest of around 100 German and ethnic circles.

"Their propaganda blamed the Jews for the German defeat in the First World War and the demands of the Treaty of Versailles. Their propagandists invoked an alleged "Jewish world conspiracy", which was to be proven with the "Protocols of the Elders of Zion". This pamphlet, which was translated into German and distributed in 100,000 copies, was a forgery by the Tsarist Russian secret service. According to this pamphlet, Jewish wise men were supposed to have planned the seizure of world domination by the Jews."

Prof. em. Dr Arno Herzig

Information on political education, Jewish life in Germany, 2012, issue 307.

In order to counteract the rampant anti-Semitism and stem the spread of the "Circles", a Republic Protection Act was passed in 1922/23. However, parties such as the DNVP (German National People's Party) used anti-Jewish propaganda for their party programmes, among other things. Anti-Semitism was also a fertile breeding ground for the founding of the NSDAP (National Socialist German Labour Party) in 1920.

On 7 December 1922, the BBV even warned of the "false prophet Dr [sic.] Hitler, the leader of the National Socialists, under the headline "The German Fascism".

Extract from: Hans-Walter Schmuhl, Bocholt in the 20th century, p. 95.

In the 1924 Reichstag election, the NSDAP received 0.3 per cent of the vote in Bocholt and in 1928 only 0.2 percentage points. The NSDAP therefore did not play a major role in Bocholt in the 1920s.

However, this changed with the global economic crisis from 1929...

1929 to 1933

Towards the end of the 1920s, the global economic crisis led to mass unemployment. Large sections of the population fell into poverty as a result. Disappointed by the democratic government of the Weimar Republic, they turned to other parties. The NSDAP in particular managed to appeal to new groups of voters on a large scale during this time, including in Bocholt.

"The founding [of the local NSDAP group] involved Bocholt factory owners who had to close their factories as a result of the global economic crisis, self-employed people, civil servants and employees."

Citation: Book of Remembrance, p. 64: Private property Josef Niebur. Transcript of a conversation with Kurt Nussbaum

on 30 April 1985 in Bocholt.

On 22 June 1930, SA members and other National Socialists from the Gau Emscher-Lippe came to Bocholt for the first time for a " advertising day". This was accompanied by fierce counter-demonstrations by the Bocholt population. Among the demonstrators was Salomon Seif, a religious official from the Jewish community in Bocholt.

The police authorities in Bocholt established that the applicant [Salomon Seif] was against the National Socialists. At the big NSDAP march in the summer of 1930, the applicant was one of the biggest agitators. He waved his stick in front of the National Socialists and also spat in front of them. This behaviour [sic] later made him unpopular with the National Socialist population of Bocholt. Seif was also suspected of circulating distorted pictures and reports of Chancellor Hitler from newspapers published in Holland in Bocholt.

Bocholt city archive, Slg newspapers, Bocholter Volksblatt,

23 June 1933, propaganda march: sheet 3, decision of the determination committee in Gelsenkirchen dated 7 December 1933.

Barely two years after this "advertising day", the NSDAP was firmly established in Bocholt. From 1932, the Bocholt local group repeatedly publicised its existence with election campaign advertisements. And with success: in the 1932 Reichstag elections, the NSDAP already achieved 9.8% of the vote.

However, despite the ever-growing share of the vote, the NSDAP had a difficult time in Bocholt. According to historian Hans-Walter Schmuhl, the National Socialists would not have been able to seize power within the city if the turnaround at Reich level had not paved the way for the dissolution of local self-government.

First boycott of Jewish shops

Adolf Hitler was appointed Reich Chancellor on 30 January 1933. With him and the NSDAP, politicians had now come to power whose party programme was clearly based on anti-Semitism. Just three days after his appointment, on 1 February 1933, Hitler had the Reichstag dissolved, effectively heralding the end of the Weimar Republic. After just a few weeks, democracy had become a dictatorship.

This dictatorship also changed the social climate. Anti-Jewish politics were openly communicated and practised.

"The Nazis marched along Königstraße, past our flat and sang anti-Semitic songs. The windows of our shop were smeared with tar, with the words 'Jew - Jewish shop'. Nazis lined up in front of the shop, took photos and prevented customers from entering the shop. [...]"

City of Bocholt. Department of Central Administration - Internal Services - Folder: Jewish fellow citizens. Harry Meier, Baltimore/USA, 26 November 1997, My memories of Bocholt.

© Stadtarchiv Bocholt

View of Osterstraße in the direction of the market squareIt therefore did not take long for the first measures against Jewish culture and Jewish fellow citizens to be implemented. As early as 1 April 1933, the first business boycott was called for under the slogan "Don't buy from Jews". Prior to this, German daily newspapers had claimed that Jews were responsible for the boycott of German goods abroad. The Bocholter Volksblatt also spread the story and the first riots broke out in Bocholt.

The propaganda of the NSDAP also quickly had an effect in Bocholt. National Socialist groups such as the NS-Volkswohlfahrt, the NS-Frauenschaft or the NS-HAGO (organisation for craftsmen and tradesmen) were founded and established themselves in the city.

At the same time, visible Jewish life was increasingly suppressed. In 1934, for example, the Israelite school was allowed to take part in the traditional St Martin's Day procession organised by the Verein für Heimatpflege Bocholt e.V. for the last time. Larger and larger sections of the population changed the way they treated and viewed their Jewish neighbours.

"The Seif family had a large family. One day, a family with small children came to visit. As the children were playing outside, a boy from Bocholt threw stones at them and shouted after them: 'There's a Jew kid wiggling his crooked little legs! The boys from Bocholt thought that was quite normal. When I told my mum, she was very shocked."

Privately owned by Josef Niebur. He conducted an interview with Mrs K.,

* 1926, lived at Rosenstiege until 1942

"In the Nazi era, neighbours and their children, with whom we had grown up, stopped greeting us from one day to the next. Acquaintances suddenly disappeared into doorways or turned round so they didn't have to greet us. That hurt a lot."

Stadtarchiv Bocholt, Slg-Zeitung, Zeno-Zeitung - Volksblatt für Bocholt und den Kreis Borken from 9 January 1935. We are building the new Germany. Transcript of a conversation with Max Lorch (Buenos Aires/Argentina) 1914 - 2002, during a visit to Bocholt on 29 July 1991.

Politically, the NSDAP appointed Emil Irrgang as the first National Socialist mayor in Bocholt on 2 January 1935. Irrgang was a staunch supporter of Nazi ideology and endeavoured to station Austrian SA troops in the same year. The so-called Austrian Legion had been expelled from the country in 1925 after a failed coup attempt. Under Irrgang, the Secret State Police was also given an office in the town of Bocholt.

Ostracisation and public harassment intensified as a result of the presence of the Austrian Legion.

"I feel like a political soldier of the Führer, who has nothing else to do but fight for the idea of National Socialism, who exemplifies National Socialism to you and brings it to complete realisation in the local administration."

Bocholt city archives, Slg newspapers: Zeno-Zeitung from 3 January 1935

I remember how Mrs Fehler [...] was often called a 'Jewish pig' by Austrian SA men when she shopped at Löwenstein. This usually happened on Saturday afternoons, because that was when the Austrian SA men from the Stadtwald camp came into town with the banner 'Whoever buys from a Jew is a traitor to the country' on their wagon, and then there was always 'something going on', i.e. the 'Austrians' were harassing people.

Private property Josef Niebur. Transcript of conversations

on 10 August/1 December 1994 with Klara Lehmbrock

(1923 - 2010), conducted by Josef Niebur and Werner Sundermann.

1935 to 1938

In January 1935, NSDAP district leader Heinrich Pfeffer called for a boycott of Jewish shops and department stores in the Bocholter Volksblatt:

[...] Of course, we are anti-Semites, and yet there are still so many Jews living in Germany. We are not against the Jews because he is a Jew, but we are against having a Jew as police chief, against Jews becoming ministers.

If the Führer decides that the struggle should be waged in this way, then we have to keep our mouths shut. It's the same with the [Jewish] department stores. We are enemies of the department stores', and the fight against them will inevitably continue. [...] Everyone must realise: If you go into a department store, you betray your fellow countrymen, the middle class, who have to fight hard for their pennies."NSDAP district leader Heinrich Pfeffer, Wir bauen das neue Deutschland, In: Stadtarchiv Bocholt, Sig. Newspapers, Zeno-Zeitung -

Volksblatt for Bocholt and the Borken district from 9 January 1935

The disenfranchisement and exclusion of Jews culminated on 15 September 1935 in the so-called "Nuremberg Race Laws". Within the laws, three individual issues were regulated and enshrined in law. The "Reichsbürgergesetz" divided the German population into "Staatsbürger" and "Reichsbürger". From then on, Jews were "citizens" without any political rights. Only "Reichsbürger" with "German or related blood" had such rights.

The "Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honour" regulated or criminalised relationships between Jewish and non-Jewish Germans. A plethora of grotesque laws and ordinances made it impossible for the Jewish population to participate in society.

The November pogrom of 1938

Jews experienced a high point of anti-Semitic violence in November 1938, when the riots, now known as the November pogrom, were triggered by the murder of the secretary of the German embassy, Ernst von Rath, by the 17-year-old Jew Herschel Grynszpan. Enraged by the deportation of his parents to the German-Polish border along with 17,000 other Polish Jews, Grynszpan forced his way into the German embassy in Paris and seriously injured von Rath.

News of the assassination spread like wildfire throughout the German Reich and was immediately used for a nationwide smear campaign against Jews.

Headlines of the Zeno-Zeitung

(Supra-regional section of the Bocholter Volksblatt) between 7 November 1938 and 9 November 1938

"Jewish assassin at the German embassy in Paris

Cowardly murder attempt - tool of world Jewry"

"The new provocation of world Jewry"

"The cowardly assassination attempt by the Jewish assassin [...]."

Spurred on and incited by the propaganda, the first pogroms were carried out by the SA and SS on the night of 8 November 1938 as a "retaliatory measure". After von Rath finally succumbed to his injuries on 9 November 1938, Reich propaganda minister Goebbels instrumentalised his death in a nationwide diatribe against Judaism. With this speech, he officially gave the starting signal for the nationwide attack on the Jewish population.

© Stadtarchiv Bocholt

August ValléeIn Bocholt, Hitler Youth extinguished the street lamps from 9.00 pm on the orders of the local NSDAP group. At around 10.30 p.m., National Socialists then marched through the city centre in several groups, destroying Jewish shops, forcibly entering private Jewish homes and vandalising the synagogue.

Very few people stood up to protect their neighbours that night. One of them was the building contractor August Vallèe, who prevented SA and SS men from entering the house of Edith Zythnik and her family at Königstraße 9 that night.

A contemporary witness report reads: "Shortly before midnight we heard a group of wild and drunk men outside the house and just a few seconds later the window panes rattled. Immediately afterwards the front door was broken down and the brown mob forced their way into the flat. They immediately went on the rampage, throwing all the china on the floor, which was then covered in broken glass. The carpets were cut up. - We were scared to death..."

"I rode my bike from home to my apprenticeship in Rhede shortly after 7.00 a.m. the morning after the so-called Reichskristallnacht. At the Westend junction I came to Villa Liebreich. The front door was open and there were several people in the villa. In the corridor or hallway, a precious Chinese vase lay smashed on the floor. A mural had been cut up several times with knives. I didn't go any further into the villa. As I had heard there that all the Jewish houses had been demolished during the night, I then drove to the synagogue. When I got to the synagogue, the outside door was open. The windows had been smashed. The synagogue looked desolate: There were bricks on the floor. The benches had been destroyed, the prayer books had been thrown on the floor and some had been torn up. The curtain in front of the Torah shrine had been torn down and was lying on the floor, as were the Torah scrolls. The stairs to the women's synagogue were unhooked. I drove from Nobelstraße to Südwall and came to Villa Friede, opposite today's adult education centre. The roof was destroyed, chair legs were sticking out. Here, too, I got into the house unhindered and went into the cellar. Most of the jars of preserved fruit had been thrown off the shelves and destroyed. I thought to myself: 'What has happened here is not right."

Transcript of an interview with Mr D. (* 1922), Bocholt, on 8 June 1993, conducted by Josef Niebur and Werner Sundermann, In: Buch der Erinnerung, p. 99.

1939 to 1941

The November pogrom of 1938 marked the beginning of a new phase in the Nazi persecution of Jews. By now at the latest, anti-Semitism and racism, including murder, had become official state policy. From today's perspective, the night of 9 November 1938 is therefore also seen as the starting point for the greatest genocide in history.

The Jewish population itself had to pay for the damage caused by the pogrom night. The so-called "Jewish property levy" was set at one billion Reichsmark by the Nazi rulers. In addition, from 9 November 1938 onwards, Jews were subjected to ever more public restrictions through laws and coercive measures. By the end of Nazi rule, almost 2,000 laws restricting Jewish life were to come into force.

The official aim of the political agenda was the complete Aryanisation of Jewish property and the complete public exclusion of Jews from social and political life.

More and more Jews decided to flee their homeland at the end of the 1930s. In 1938 alone, 60 Bocholters of Jewish faith left the city. 29 of them fled between the night of the pogrom and the end of the year alone.

Those who stayed had a variety of reasons for doing so: Over time, it became increasingly difficult for adults in particular to obtain all the necessary documents and travel papers, as many countries restricted migration. After years of disenfranchisement, many families lacked the necessary financial means to leave the country. However, some people simply refused to leave their homes, their birthplaces or their families. They desperately hoped for an end to the reign of terror.

But this longed-for end never materialised. Instead, all political precautions were now taken that would lead to the so-called "Final Solution to the Jewish Question" in the sense of the murder of European Jews in the German sphere of influence.

Establishment of the Jewish Houses

© Stadtarchiv Bocholt

Jewish housesWith the enactment of the " law on tenancies for Jews on 30 April 1939", Jews were largely unprotected against evictions. As a result, the first so-called Jews' houses were set up in Bocholt. The forced relocation of all Jews to "Jewish houses" meant that they were now completely isolated from the rest of the population, removed from their traditional neighbourhoods and deprived of their homes. Their homes were then made available to "Aryan" families.

"According to my recollection, the Jews still living in Bocholt had to move to Stiftstraße 32, three houses down from my parents' house, in 1939 or 1940. A total of 10 to 12 people were crammed into this large, two-storey house. [...] As soon as the Jews moved into the house at Stiftstraße 32, my father Carl Becks received a written order from the Bocholt city council to supply the Jews still in the city with the most basic foodstuffs.

He was only allowed to sell the Jews rations that were considerably smaller than those of the rest of the population. The Jews were excluded from the sale of special rations as well as tobacco products, coffee and alcohol. Nevertheless, they also received these from my father. The Jews came to him across the field in the evening or at night, for example Mr Hochheimer received cigarettes. They were only allowed to buy from us at certain times - daily from 1.00 pm to 2.00 pm and from 5.00 pm to 6.00 pm. No other customers were allowed in the shop during these times. [...]"

Private property Josef Niebur. Transcript of an interview with Mrs Inge Becks (* 1926), Bocholt, on 10 December 1993, conducted by Werner Sundermann and Josef Niebur

"Jewish houses" as a starting point for deportations

In addition to the displacement of Jews from their traditional neighbourhoods, control and surveillance also played an important role in the establishment of the "Jewish Houses". However, the mere concentration of Jews and the associated harassment of Jews was no longer enough for the Nazi rulers. Instead, they aimed to completely "remove" all European Jews from the German sphere of influence.

To this end, labour and concentration camps as well as ghettos were set up after the beginning of the Second World War and the associated expansion of the German sphere of influence, particularly in Eastern Europe. The camps as well as the ghettos were complete areas sealed off from the outside world in which Jews were exploited, abused and murdered under inhumane conditions.

The deportations to the Riga ghetto were a further step into an uncertain future for those affected. Fear and uncertainty accompanied the victims. The first trains travelled from the German Reich to the ghettos and extermination camps of Eastern Europe in October 1941. Prior to this, the people were concentrated at central collection points. In Bocholt, the buses and lorries set off early in the morning of 10 December 1941 to forcibly collect 26 Jews.

As I do almost every morning, I drove through Niederbruch. On this cold December morning, I immediately noticed a group of men standing in front of the Metzger family's house. The men had badges on their arms. As I got closer, I saw that they were taking Metzgers out of the house.

The Metzgers were beaten; the women were crying. There was fear on the Jews' faces, they were resisting. But the men shouted at them. [...] The Jews had to get on the bus."

Private property Josef Niebur. Transcript of an interview with Luzia Sundermann (née Branse, 1901-1993), Bocholt, conducted by her son Werner Sundermann and Josef Niebur on 2 December 1987

"One day - it may have been in December 1941 - while I was serving customers, I saw a large group of people in poor clothing walking past on the opposite side of the street, all carrying suitcases.

The group walked round the police building onto Königsmühlenweg. A short time later, I saw a bus and a lorry with an open loading area driving from there to the right, in the direction of Rhede. The people I had just seen had obviously got on the bus. [...]"

Transcript of an interview with Ernst (* 1921) and

Gertrud (* 1919) Deutmeyer, Rhede, on 9 December 1989,

conducted by Josef Niebur and Werner Sundermann.

Excerpt from the city chronicle of 10 December 1941

"On the orders of the Secret State Police, 26 Jews* were deported from Bocholt to Riga.

The deportation took place on [...] day, in the morning, by a bus provided by the police administration in Bocholt. The luggage was transported to Münster on the trailer of a lorry. The costs were borne by the Secret State Police.

Securities, foreign currency, savings bank books etc., valuables of any kind (gold, silver, platinum, with the exception of wedding rings) were not allowed to be taken along. The deported Jews were also required to take tools of the trade (spades, hoes, scales, etc.) with them. The majority of Jews took these tools with them.

Bicycles, binoculars, typewriters, cameras, etc., over which the State Police had reserved the right of disposal, were provisionally seized at the local police station. Between 7.00 a.m. and about 8.30 a.m., the bus provided by the local police authority drove up to the houses where the Jews lived."

* Originally, 27 Jews from Bocholt were to be deported to Münster on 10 December 1941. However, Amalie Markus attempted to take her own life on 9 December 1941 by drinking vinegar essence in view of the announced deportation. She died as a result of her suicide attempt on 16 December 1941 in Rheder Hospital.

%20_%20gemeinfrei%20.jpg?height=347&width=495)